Film speed

Film speed is the measure of a photographic film's sensitivity to light, determined by sensitometry and measured on various numerical scales, the most recent being the ISO system. Relatively insensitive film, with a correspondingly lower speed index requires more exposure to light to produce the same image density as a more sensitive film, and is thus commonly termed a slow film. Highly sensitive films are correspondingly termed fast films. A closely related ISO system is used to measure the sensitivity of digital imaging systems. In both digital and film photography, the reduction of exposure corresponding to use of higher sensitivities generally leads to reduced image quality (via coarser film grain or higher image noise of other types). Basically, the higher the film speed, the worse the photo quality.

Contents |

Film speed systems

There have been many systems of denoting film sensitivity.

Historic systems

The former American Standards Association (ASA) and the German Institute for Standardization (DIN) each promulgated film speed standards that have now been combined into the current ISO standard (see below).

The British Standards Institute produced their own scale. It was for all practical purposes identical to the DIN system except that the BS number was always 10 greater than the DIN number. It may be that similarity that lead to its rapid demise.

GOST (Russian: ГОСТ) is an arithmetic scale which was used in the former Soviet Union before 1987. It is almost identical to the ASA standard, having been based on a speed point at a density 0.2 above base plus fog, as opposed to the ASA's 0.1.[1] After 1987, the GOST scale was aligned to the ISO scale. GOST markings are only found on pre-1987 photographic equipment (film, cameras, lightmeters, etc.) of Soviet Union manufacture[2].

Current ISO system

The current International Standard for measuring the speed of color negative film is called ISO 5800:1987[3] from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Related standards ISO 6:1993[4] and ISO 2240:2003[5] define scales for speeds of black-and-white negative film and color reversal film. This system defines both an arithmetic and a logarithmic scale, combining the previously separate ASA and DIN systems.[6]

In the ISO arithmetic scale, corresponding to the ASA system, a doubling of the sensitivity of a film requires a doubling of the numerical film speed value. In the ISO logarithmic scale, which corresponds to the DIN scale, adding 3° to the numerical value that designates the film speed constitutes a doubling of that value. For example, a film rated ISO 200/24° is twice as sensitive as a film rated ISO 100/21°.[6]

Commonly, the logarithmic speed is omitted, and only the arithmetic speed is given; for example, “ISO 100”.[7]

Conversion between current scales

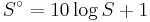

Conversion from the logarithmic DIN speed S° to the arithmetic ASA speed S, as given by[8] requires the following calculation:

and rounding to the nearest standard arithmetic speed in Table 1 below. By simple rearrangement, conversion from arithmetic speed to logarithmic speed is given by

and rounding to the nearest integer. Here the log function is base 10.

| ISO arithmetic scale (ASA scale) |

ISO log scale (DIN scale) |

GOST (Soviet pre-1987) |

Example of film stock with this nominal speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 9° | original Kodachrome | |

| 8 | 10° | Polaroid PolaBlue | |

| 10 | 11° | Kodachrome 8 mm film | |

| 12 | 12° | 11 | Gevacolor 8 mm reversal film, later Agfa Dia-Direct |

| 16 | 13° | 11 | Agfacolor 8 mm reversal film |

| 20 | 14° | 16 | Adox CMS 20 |

| 25 | 15° | 22 | old Agfacolor, Kodachrome II and (later) Kodachrome 25 |

| 32 | 16° | 22 | Kodak Panatomic-X |

| 40 | 17° | 32 | Kodachrome 40 (movie) |

| 50 | 18° | 45 | Fuji RVP (Velvia), Ilford Pan F Plus, Kodak Vision2 50D 5201 (movie) |

| 64 | 19° | 45 | Kodachrome 64, Ektachrome-X |

| 80 | 20° | 65 | Ilford Commercial Ortho |

| 100 | 21° | 90 | Kodacolor Gold, Kodak T-Max (TMX), Provia |

| 125 | 22° | 90 | Ilford FP4+, Kodak Plus-X Pan |

| 160 | 23° | 130 | Fujicolor Pro 160C/S, Kodak High-Speed Ektachrome, Kodak Portra 160NC and 160VC |

| 200 | 24° | 180 | Fujicolor Superia 200, Agfa Scala 200x |

| 250 | 25° | 180 | Tasma Foto-250 |

| 320 | 26° | 250 | Kodak Tri-X Pan Professional (TXP) |

| 400 | 27° | 350 | Kodak T-Max (TMY), Tri-X 400, Ilford HP5+, Fujifilm Superia X-tra 400 |

| 500 | 28° | 350 | Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 (movie) |

| 640 | 29° | 560 | Polaroid 600 |

| 800 | 30° | 700 | Fuji Pro 800Z |

| 1000 | 31° | 700 | Kodak P3200 TMAX, Ilford Delta 3200 (see Marketing anomalies below) |

| 1250 | 32° | Kodak Royal-X Panchromatic | |

| 1600 | 33° | 1400–1440 | Fujicolor 1600 |

| 2000 | 34° | ||

| 2500 | 35° | ||

| 3000 | ~36° | Polaroid Black and White 'Peel apart' Film | |

| 3200 | 36° | 2800–2880 | Kodak T-Max (TMZ) (achieved by push processing), Konica 3200 |

| 4000 | 37° | ||

| 5000 | 38° | ||

| 6400 | 39° | ||

| 12,800 | 42° | Values at this speed and above are ISO equivalents on digital cameras[Table Note 3] | |

| 25,600 | 45° | ||

| 51,200 | 48° | ||

| 102,400 | 51° | First commercial digital SLR cameras with this ISO equivalent: Nikon D3S and Canon EOS-1D Mark IV (2009) |

Table Notes

- ISO arithmetic speeds from 6 to 6400 are taken from ISO 12232:1998 (Table 1, p. 9).

- ISO arithmetic speeds from 12,800 to 102,400 are from specifications by Canon[9] and Nikon.[10]

- ISO 12232:1998 does not specify speeds greater than 10,000. However, the upper limit for Snoise 10,000 is given as 12,500, suggesting that ISO may have envisioned a progression of 12,500, 25,000, 50,000, and 100,000, similar to that from 1250 to 10,000. This is consistent with ASA PH2.12-1961 (Table 2, p. 9), which showed (but did not specify) a speed of 12,500 as the next full step greater than 6400. Canon and Nikon apparently chose to continue an exact power-of-2 progression from the highest previously realized speed, 6400. Because the precise speed values are based on a uniform power-of-2 progression and rounded to convenient values close to the nearest 1/3 step, the actual sensitivities are likely the same with either progression.

Determining film speed

Film speed is found from a plot of optical density vs. log of exposure for the film, known as the D–log H curve or Hurter–Driffield curve. There typically are five regions in the curve: the base + fog, the toe, the linear region, the shoulder, and the overexposed region. For black and white negative film, the “speed point” m is the point on the curve where density exceeds the base + fog density by 0.1 when the negative is developed so that a point n where the log of exposure is 1.3 units greater than the exposure at point m has a density 0.8 greater than the density at point m. The exposure Hm, in lux-s, is that for point m when the specified contrast condition is satisfied. The ISO arithmetic speed is determined from

;

;

this value is then rounded to the nearest standard speed in Table 1 of ISO 6:1993.

Determining speed for color negative film is similar in concept but more complex because it involves separate curves for blue, green, and red. The film is processed according to the film manufacturer’s recommendations rather than to a specified contrast. ISO speed for color reversal film is determined from the middle rather than the threshold of the curve; it again involves separate curves for blue, green, and red, and the film is processed according to the film manufacturer’s recommendations.

Applying film speed

Film speed is used in the exposure equations to find the appropriate exposure parameters. Four variables are available to the photographer to obtain the desired effect: lighting, film speed, f-number (aperture size), and shutter speed (exposure time). The equation may be expressed as ratios, or, by taking the logarithm (base 2) of both sides, by addition, using the APEX system, in which every increment of 1 is a doubling of exposure; this increment is commonly known as a "stop". The effective f-number is proportional to the ratio between the lens focal length and aperture diameter, the diameter itself being proportional to the square root of the aperture area. Thus, a lens set to f/1.4 allows twice as much light to strike the focal plane as a lens set to f/2. Therefore, each f-number factor of the square root of two (approximately 1.4) is also a stop, so lenses are typically marked in that progression: f/1.4, 2, 2.8, 4, 5.6, 8, 11, 16, 22, 32, etc.

Commonly stated values for exposure parameters are rounded to convenient values that are easy to remember; however, the actual values to be used in exposure calculations are in exact power-of-2 progressions.[11]

Exposure index

Exposure index, or EI, refers to speed rating assigned to a particular film and shooting situation in variance to the film's actual speed. It is used to compensate for equipment calibration inaccuracies or process variables, or to achieve certain effects. The exposure index may simply be called the speed setting, as compared to the speed rating.

For example, a photographer may rate an ISO 400 film at EI 800 and then use push processing to obtain printable negatives in low-light conditions. The film has been exposed at EI 800.

Another example occurs where a camera's shutter is miscalibrated and consistently overexposes or underexposes the film; similarly, a light meter may be inaccurate. One may adjust the EI rating accordingly in order to compensate for these defects and consistently produce correctly exposed negatives.

Reciprocity

Upon exposure, the amount of light energy that reaches the film determines the effect upon the emulsion. If the brightness of the light is multiplied by a factor and the exposure of the film decreased by the same factor by varying the camera's shutter speed and aperture, so that the energy received is the same, the film will be developed to the same density. This rule is called reciprocity. The systems for determining the sensitivity for an emulsion are possible because reciprocity holds. In practice, reciprocity works reasonably well for normal photographic films for the range of exposures between 1/1000 second to 1/2 second. However, this relationship breaks down outside these limits, a phenomenon known as reciprocity failure.[12]

Film sensitivity and grain

Film speed is roughly related to granularity, the size of the grains of silver halide in the emulsion, since larger grains give film a greater sensitivity to light. Fine-grain stock, such as portrait film or those used for the intermediate stages of copying original camera negatives, is "slow", meaning that the amount of light used to expose it must be high or the shutter must be open longer. Fast films, used for shooting in poor light or for shooting fast motion, produce a grainier image. Each grain of silver halide develops in an all-or-nothing way into dark silver or nothing. Thus, each grain is a threshold detector; in aggregate, their effect can be thought of as a noisy nonlinear analog light detector.

Kodak has defined a "Print Grain Index" (PGI) to characterize film grain (color negative films only), based on perceptual just noticeable difference of graininess in prints. They also define "granularity", a measurement of grain using an RMS measurement of density fluctuations in uniformly-exposed film, measured with a microdensitometer with 48 micrometre aperture.[13] Granularity varies with exposure — underexposed film looks grainier than overexposed film.

Use of grain

In advertising, music videos, and some drama, mismatches of grain, color cast, and so forth between shots are often deliberate and added in post-production.

Marketing anomalies

Some high-speed black-and-white films, such as Ilford Delta 3200 and Kodak T-MAX P3200, are marketed with film speeds in excess of their true ISO speed as determined using the ISO testing method. For example, the Ilford product is actually an ISO 1000 film, according to its data sheet. The manufacturers do not indicate that the 3200 number is an ISO rating on their packaging.[14] Kodak and Fuji also marketed E6 films designed for pushing (hence the "P" prefix), such as Ektachrome P800/1600 and Fujichrome P1600, both with a base speed of ISO 400.

Digital camera ISO speed and exposure index

In digital camera systems, an arbitrary relationship between exposure and sensor data values can be achieved by setting the signal gain of the sensor. The relationship between the sensor data values and the lightness of the finished image is also arbitrary, depending on the parameters chosen for the interpretation of the sensor data into an image color space such as sRGB.

For digital photo cameras ("digital still cameras"), an exposure index (EI) rating—commonly called ISO setting—is specified by the manufacturer such that the sRGB image files produced by the camera will have a lightness similar to what would be obtained with film of the same EI rating at the same exposure. The usual design is that the camera's parameters for interpreting the sensor data values into sRGB values are fixed, and a number of different EI choices are accommodated by varying the sensor's signal gain in the analog realm, prior to conversion to digital. Some camera designs provide at least some EI choices by adjusting the sensor's signal gain in the digital realm. A few camera designs also provide EI adjustment through a choice of lightness parameters for the interpretation of sensor data values into sRGB; this variation allows different tradeoffs between the range of highlights that can be captured and the amount of noise introduced into the shadow areas of the photo.

Digital cameras have far surpassed film in terms of sensitivity to light, with ISO equivalent speeds of up to 102,400, a number that is unfathomable in the realm of conventional film photography. Faster processors, as well as advances in software noise reduction techniques allow this type of processing to be executed the moment the photo is captured, allowing photographers to store images that have a higher level of refinement and would have been prohibitively time consuming to process with earlier generations of digital camera hardware.

The ISO 12232:2006 standard

The ISO standard 12232:2006[15] gives digital still camera manufacturers a choice of five different techniques for determining the exposure index rating at each sensitivity setting provided by a particular camera model. Three of the techniques in ISO 12232:2006 are carried over from the 1998 version of the standard, while two new techniques allowing for measurement of JPEG output files are introduced from CIPA DC-004.[16] Depending on the technique selected, the exposure index rating can depend on the sensor sensitivity, the sensor noise, and the appearance of the resulting image. The standard specifies the measurement of light sensitivity of the entire digital camera system and not of individual components such as digital sensors, although Kodak has reported[17] using a variation to characterize the sensitivity of two of their sensors in 2001.

The Recommended Exposure Index (REI) technique, new in the 2006 version of the standard, allows the manufacturer to specify a camera model’s EI choices arbitrarily. The choices are based solely on the manufacturer’s opinion of what EI values produce well-exposed sRGB images at the various sensor sensitivity settings. This is the only technique available under the standard for output formats that are not in the sRGB color space. This is also the only technique available under the standard when multi-zone metering (also called pattern metering) is used.

The Standard Output Specification (SOS) technique, also new in the 2006 version of the standard, effectively specifies that the average level in the sRGB image must be 18% gray plus or minus 1/3 stop when exposed per the EI with no exposure compensation. Because the output level is measured in the sRGB output from the camera, it is only applicable to sRGB images—typically JPEG—and not to output files in raw image format. It is not applicable when multi-zone metering is used.

The CIPA DC-004 standard requires that Japanese manufacturers of digital still cameras use either the REI or SOS techniques. Consequently, the three EI techniques carried over from ISO 12232:1998 are not widely used in recent camera models (approximately 2007 and later). As those earlier techniques did not allow for measurement from images produced with lossy compression, they cannot be used at all on cameras that produce images only in JPEG format.

The saturation-based technique is closely related to the SOS technique, with the sRGB output level being measured at 100% white rather than 18% gray. The saturation-based value is effectively 0.704 times the SOS value.[18] Because the output level is measured in the sRGB output from the camera, it is only applicable to sRGB images—typically TIFF—and not to output files in raw image format. It is not applicable when multi-zone metering is used.

The two noise-based techniques have rarely been used for consumer digital still cameras. These techniques specify the highest EI that can be used while still providing either an “excellent” picture or a “usable” picture depending on the technique chosen.

Measurements and calculations

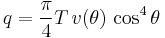

ISO speed ratings of a digital camera are based on the properties of the sensor and the image processing done in the camera, and are expressed in terms of the luminous exposure H (in lux seconds) arriving at the sensor. For a typical camera lens with an effective focal length f that is much smaller than the distance between the camera and the photographed scene, H is given by

where L is the luminance of the scene (in candela per m²), t is the exposure time (in seconds), N is the aperture f-number, and

is a factor depending on the transmittance T of the lens, the vignetting factor v(θ), and the angle θ relative to the axis of the lens. A typical value is q = 0.65, based on θ = 10°, T = 0.9, and v = 0.98.[19]

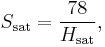

Saturation-based speed

The saturation-based speed is defined as

where  is the maximum possible exposure that does not lead to a clipped or bloomed camera output. Typically, the lower limit of the saturation speed is determined by the sensor itself, but with the gain of the amplifier between the sensor and the A/D-converter, the saturation speed can be increased. The factor 78 is chosen such that exposure settings based on a standard light meter and an 18-percent reflective surface will result in an image with a grey level of 18%/√2 = 12.7% of saturation. The factor √2 indicates that there is half a stop of headroom to deal with specular reflections that would appear brighter than a 100% reflecting white surface.

is the maximum possible exposure that does not lead to a clipped or bloomed camera output. Typically, the lower limit of the saturation speed is determined by the sensor itself, but with the gain of the amplifier between the sensor and the A/D-converter, the saturation speed can be increased. The factor 78 is chosen such that exposure settings based on a standard light meter and an 18-percent reflective surface will result in an image with a grey level of 18%/√2 = 12.7% of saturation. The factor √2 indicates that there is half a stop of headroom to deal with specular reflections that would appear brighter than a 100% reflecting white surface.

Noise-based speed

The noise-based speed is defined as the exposure that will lead to a given signal-to-noise ratio on individual pixels. Two ratios are used, the 40:1 ("excellent image quality") and the 10:1 ("acceptable image quality") ratio. These ratios have been subjectively determined based on a resolution of 70 pixels per cm (180 DPI) when viewed at 25 cm (10 inch) distance. The signal-to-noise ratio is defined as the standard deviation of a weighted average of the luminance (overall brightness) and color of individual pixels. The noise-based speed is mostly determined by the properties of the sensor and somewhat affected by the noise in the electronic gain and AD converter.

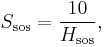

Standard output sensitivity (SOS)

In addition to the above speed ratings, the standard also defines the standard output sensitivity (SOS), how the exposure is related to the digital pixel values in the output image. It is defined as

where  is the exposure that will lead to values of 118 in 8-bit pixels, which is 18 percent of the saturation value in images encoded as sRGB or with gamma = 2.2.

is the exposure that will lead to values of 118 in 8-bit pixels, which is 18 percent of the saturation value in images encoded as sRGB or with gamma = 2.2.

Discussion

The standard specifies how speed ratings should be reported by the camera. If the noise-based speed (40:1) is higher than the saturation-based speed, the noise-based speed should be reported, rounded downwards to a standard value (e.g. 200, 250, 320, or 400). The rationale is that exposure according to the lower saturation-based speed would not result in a visibly better image. In addition, an exposure latitude can be specified, ranging from the saturation-based speed to the 10:1 noise-based speed. If the noise-based speed (40:1) is lower than the saturation-based speed, or undefined because of high noise, the saturation-based speed is specified, rounded upwards to a standard value, because using the noise-based speed would lead to overexposed images. The camera may also report the SOS-based speed (explicitly as being an SOS speed), rounded to the nearest standard speed rating.

For example, a camera sensor may have the following properties:  ,

,  , and

, and  . According to the standard, the camera should report its sensitivity as

. According to the standard, the camera should report its sensitivity as

- ISO 100 (daylight)

- ISO speed latitude 50–1600

- ISO 100 (SOS, daylight).

The SOS rating could be user controlled. For a different camera with a noisier sensor, the properties might be  ,

,  , and

, and  . In this case, the camera should report

. In this case, the camera should report

- ISO 200 (daylight),

as well as a user-adjustable SOS value. In all cases, the camera should indicate for the white balance setting for which the speed rating applies, such as daylight or tungsten (incandescent light).

Despite these detailed standard definitions, cameras typically do not clearly indicate whether the user "ISO" setting refers to the noise-based speed, saturation-based speed, or the specified output sensitivity, or even some made-up number for marketing purposes. Because the 1998 version of ISO 12232 did not permit measurement of camera output that had lossy compression, it was not possible to correctly apply any of those measurements to cameras that did not produce sRGB files in an uncompressed format such as TIFF. Following the publication of CIPA DC-004 in 2006, Japanese manufacturers of digital still cameras are required to specify whether a sensitivity rating is REI or SOS.

As should be clear from the above, a greater SOS setting for a given sensor comes with some loss of image quality, just like with analog film. However, this loss is visible as image noise rather than grain. Current (January 2010) APS and 35mm sized digital image sensors, both CMOS and CCD based, do not produce significant noise until about ISO 1600.

See also

- APEX system

- Lens speed

- Sensitometry is the scientific study of light-sensitive materials, especially photographic film.

References

- ↑ Leslie Stroebel and Richard D. Zakia (1995). The Focal Encyclopedia of Photograph. Focal Press. p. 304. ISBN 9780240514178. http://books.google.com/books?id=CU7-2ZLGFpYC&pg=PA304&dq=Russian+Standards+Association+GOST++film-speed&lr=&as_brr=3&ei=t0XSSYfrEoyokAT78JymBw.

- ↑ Krasnogorsky Zavod,. "Center site. Questions and answers: Film speeds (translated with Google}". http://translate.google.co.uk/translate?hl=en&sl=ru&u=http://www.zenitcamera.com/qa/qa-filmspeeds.html. Retrieved 26 January, 2010.

- ↑ "ISO 5800:1987: Photography – Colour negative films for still photography – Determination of ISO speed". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=11948.

- ↑ "ISO 6:1993: Photography – Black-and-white pictorial still camera negative film/process systems – Determination of ISO speed". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=3580.

- ↑ "ISO 2240:2003: Photography – Colour reversal camera films – Determination of ISO speed". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=34533.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 R. E. Jacobson, Sidney F. Ray, Geoffrey G. Attridge, and Norman R. Axford (2000). The manual of photography. Focal Press. p. 305–307. ISBN 9780240515748. http://books.google.com/books?id=MblHnLN2N2kC&pg=PA306&dq=ISO+5800-1987&ei=X0HSSaPCN4bgkQTooe3bBA#PPA306,M1.

- ↑ Carson Graves (1996). The zone system for 35mm photographers. Focal Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780240802039. http://books.google.com/books?id=nHgZHXvqy5sC&pg=PA124&dq=ISO+ASA+logarithmic+film+speed&lr=&as_drrb_is=q&as_minm_is=1&as_miny_is=2009&as_maxm_is=12&as_maxy_is=2009&as_brr=0&as_pt=ALLTYPES&ei=YD7SSZ_xI4HKkATf0PWfBg.

- ↑ ISO 2721:1982. Photography — Cameras — Automatic controls of exposure (paid download). Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- ↑ Canon USA web page for Canon EOS-1D Mark IV. Accessed 11 January 2010.

- ↑ Nikon USA web page for Nikon D3s. Accessed 11 January 2010.

- ↑ ANSI PH3.49-1971 (Table 2, p. 8) gave the precise value of f/2.8 as

; ASA PH2.12-1961 (Table 2, p. 9) additionally gave the precise value of ASA 25 speed as

; ASA PH2.12-1961 (Table 2, p. 9) additionally gave the precise value of ASA 25 speed as ![\sqrt[3] 2](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/eca0e705b1d86d4b1542e5d33b6f1d73.png) , implying that standard speeds that were integral powers of 2 were exact. The current standard, ISO 2720:1974, does not state the precise values.

, implying that standard speeds that were integral powers of 2 were exact. The current standard, ISO 2720:1974, does not state the precise values. - ↑ Ralph W. Lambrecht and Chris Woodhouse (2003). Way Beyond Monochrome. Newpro UK Ltd. p. 113. ISBN 9780863433542. http://books.google.com/books?id=Q7M0zOHcUxsC&pg=PA113&dq=Abney+Schwarzschild+reciprocity+failure&lr=&as_brr=3&as_pt=ALLTYPES&ei=UYCnSfmIJ5ykkQTh4cSdBA.

- ↑ "Kodak Tech Pub E-58: Print Grain Index". Eastman Kodak, Professional Division. July 2000. http://www.kodak.com/global/en/professional/support/techPubs/e58/e58.jhtml.

- ↑ Fact Sheet, Delta 3200 Professional (PDF). Knutsford, U.K.: Ilford Photo.

- ↑ ISO 12232:2006. Photography — Digital still cameras — Determination of exposure index, ISO speed ratings, standard output sensitivity, and recommended exposure index (paid download). Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- ↑ CIPA DC-004. Sensitivity of digital cameras. Tokyo: Camera & Imaging Products Association.

- ↑ Kodak Image Sensors – ISO Measurement. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak.

- ↑ New Measures of the Sensitivity of a Digital Camera. Douglas A. Kerr, P.E., August 30, 2007.

- ↑ ISO 12232:1998. Photography — Electronic still-picture cameras — Determination of ISO speed, p. 12.

- ASA PH2.12-1961. American Standard, General-Purpose Photographic Exposure Meters (photoelectric type). New York: American Standards Association. Superseded by ANSI PH3.49-1971.

- ANSI PH3.49-1971. American National Standard for general-purpose photographic exposure meters (photoelectric type). New York: American National Standards Institute. After several revisions, this standard was withdrawn in favor of ISO 2720:1974.

- ISO 2720:1974. General Purpose Photographic Exposure Meters (Photoelectric Type) – Guide to Product Specification. International Organization for Standardization.

- Leslie Stroebel, John Compton, Ira Current, and Richard Zakia. Basic Photographic Materials and Processes, second edition. Boston: Focal Press, 2000. ISBN 0-240-80405-8.

External links

- The official ISO 6:1993 (black-and-white negative films; paid download).

- The official ISO 2240:2003 (color reversal films; paid download).

- The official ISO 5800:1987 (color negative films; paid download).

- The official ISO 12232:2006 (digital still cameras; paid download).

- What is the meaning of ISO for digital cameras? Digital Photography FAQ

- Signal-dependent noise modeling, estimation, and removal for digital imaging sensors

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||